mirror of

https://codeberg.org/Mo8it/How_To_Linux.git

synced 2024-12-05 01:40:32 +00:00

Compare commits

5 commits

12b74dbe8f

...

fabb98c5a5

| Author | SHA1 | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| fabb98c5a5 | |||

| ca5f42d273 | |||

| dcd6450a42 | |||

| f37fe50656 | |||

| edda5caced |

10 changed files with 1496 additions and 36 deletions

1

.gitignore

vendored

1

.gitignore

vendored

|

|

@ -1 +1,2 @@

|

|||

/book

|

||||

target/

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

@ -630,7 +630,7 @@ state the exclusion of warranty; and each file should have at least

|

|||

the "copyright" line and a pointer to where the full notice is found.

|

||||

|

||||

How_To_Linux

|

||||

Copyright (C) 2022 Mohamad Bitar

|

||||

Copyright (C) 2023 Mo Bitar (@mo8it)

|

||||

|

||||

This program is free software: you can redistribute it and/or modify

|

||||

it under the terms of the GNU Affero General Public License as published

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

2

cs/.ignore

Normal file

2

cs/.ignore

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,2 @@

|

|||

Cargo.lock

|

||||

/LICENSE.txt

|

||||

1352

cs/Cargo.lock

generated

Normal file

1352

cs/Cargo.lock

generated

Normal file

File diff suppressed because it is too large

Load diff

11

cs/Cargo.toml

Normal file

11

cs/Cargo.toml

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,11 @@

|

|||

[package]

|

||||

name = "cs"

|

||||

publish = false

|

||||

authors = ["Mo Bitar <mo8it@proton.me>"]

|

||||

version = "0.1.0"

|

||||

edition = "2021"

|

||||

license = "AGPL-3.0"

|

||||

repository = "https://codeberg.org/mo8it/dev-tools"

|

||||

|

||||

[dependencies]

|

||||

collective-score-client = "0.0.2"

|

||||

15

cs/src/day1/collective_score_intro.rs

Normal file

15

cs/src/day1/collective_score_intro.rs

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,15 @@

|

|||

use collective_score_client::{

|

||||

check::{Check, IntoTask, RunnableCheck},

|

||||

validator::{stdin::Stdin, string_content::StringContent},

|

||||

};

|

||||

|

||||

pub fn task() -> (&'static str, Box<dyn RunnableCheck>) {

|

||||

Check::builder()

|

||||

.description("Checking stdin")

|

||||

.validator(Stdin {

|

||||

expected: StringContent::Full("OK\n"),

|

||||

})

|

||||

.hint("Did you pipe `echo \"OK\"` into this command?")

|

||||

.build()

|

||||

.into_task("collective-score-intro")

|

||||

}

|

||||

7

cs/src/day1/mod.rs

Normal file

7

cs/src/day1/mod.rs

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

|||

mod collective_score_intro;

|

||||

|

||||

use collective_score_client::check::RunnableCheck;

|

||||

|

||||

pub fn tasks() -> [(&'static str, Box<dyn RunnableCheck>); 1] {

|

||||

[collective_score_intro::task()]

|

||||

}

|

||||

17

cs/src/main.rs

Normal file

17

cs/src/main.rs

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,17 @@

|

|||

mod day1;

|

||||

|

||||

use collective_score_client::run;

|

||||

use std::process;

|

||||

|

||||

fn main() {

|

||||

let tasks = day1::tasks().into_iter().collect();

|

||||

|

||||

if let Err(e) = run(

|

||||

tasks,

|

||||

"collective-score-dev-tools",

|

||||

"https://collective-score.mo8it.com",

|

||||

) {

|

||||

eprintln!("{e:?}");

|

||||

process::exit(1);

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

|

@ -4,49 +4,84 @@ So far, we did only use commands that are common in every Linux system.

|

|||

|

||||

Now, we want to start exploring additional commands that might not be preinstalled on your system.

|

||||

|

||||

Therefore, we need to learn how to install so called packages to get access to additional programs.

|

||||

Therefore, we need to learn how to install so called _packages_ to get access to additional programs.

|

||||

|

||||

### Package managers

|

||||

|

||||

In Linux, you don't install programs by using a search engine to find a website, then visit the website and download an installer, then run the installer and click "Next" and "Agree" repeatedly without even reading what you are agreeing to 🤮

|

||||

|

||||

This method is too insecure. You have to trust the website that you did visit. You have to hope that no malware is delivered while you are downloading the installer from the website. You can get the malware either from the website itself or through a man-in-the-middle attack. Then the installer might do whatever it wants. You just click "Next" and suddenly your system shows you (extra) ads or your browser search preferences are overwritten by Yahoo. Surprise! 🎉

|

||||

This method is too inconvinient and insecure.

|

||||

You have to trust the website that you visit.

|

||||

You have to hope that no malware is delivered while you are downloading the installer from the website.

|

||||

You can get the malware either from the website itself or through a man-in-the-middle attack.

|

||||

Then the installer might do whatever it wants.

|

||||

You just click "Next" and suddenly your system shows you (extra) ads or your browser search preferences are overwritten by Yahoo.

|

||||

Surprise! 🎉

|

||||

|

||||

In Linux, you (mainly) install software through the package manager that ships with your distribution. The software is then downloaded from a repository which is a collection of packages that is managed by the distribution. The distribution managers make sure that no malware is added to their repositories.

|

||||

In Linux, you (mainly) install software through the package manager that is shipped with your distribution.

|

||||

The software is then downloaded from a repository which is a collection of packages that is managed by the distribution.

|

||||

The distribution managers make sure that no malware is added to their repositories.

|

||||

|

||||

The package manager does take care of verifying the downloaded packages before installation. This is done using some cryptographic methods and prevents man-in-the-middle attacks or installation of packages that were corrupted during the download process.

|

||||

A package manager takes care of verifying the downloaded packages before installation.

|

||||

This is done using some cryptographic methods and prevents man-in-the-middle attacks or installation of packages that were corrupted during the download process.

|

||||

|

||||

The package manager does also take care of installing any other packages that you did not specify but are required by the package that you want to install. These packages are called dependencies.

|

||||

The package manager does also take care of installing any other packages that you did not specify but are required by the package that you want to install.

|

||||

These packages are called _dependencies_.

|

||||

|

||||

Since this book uses a [Fedora](https://getfedora.org) system for demonstrations, the book will use Fedora's package manager `dnf`.

|

||||

Since this course uses a [Fedora](https://getfedora.org) system for its demonstrations, we will use Fedora's package manager `dnf`.

|

||||

|

||||

If you are using another Linux distribution, you might need to replace the commands of `dnf` with `apt` for Debian based distributions for example.

|

||||

|

||||

It is important to understand the functionality of package managers. Then you can transfer this knowledge to other package managers if required. This applies to some other aspects in Linux too, since _the Linux operating system_ does not exist. There are distributions that bundle a set of software and differ in small ways.

|

||||

It is important to understand the functionality of package managers.

|

||||

Then you can transfer this knowledge to other package managers if required.

|

||||

|

||||

To install a package, you need administrative privileges. Therefore, we need some `sudo` powers. `sudo` will be explained in the next section.

|

||||

This applies to some other aspects in Linux too, since _**the** Linux operating system_ does not exist.

|

||||

There are distributions that bundle a set of software and differ in small ways.

|

||||

|

||||

Let's install our first package! To do so, enter `sudo dnf install cmatrix`. You will be asked for the password of your user. Type the password and then press `Enter`. For security reasons, you will not be able to see you password while entering it. So don't wonder why nothing happens while typing the password. Just type it and then press `Enter`.

|

||||

To install a package, you need administrative privileges.

|

||||

Therefore, we need some `sudo` powers.

|

||||

`sudo` will be explained in the next section.

|

||||

|

||||

The package manager might need some time to synchronize some data, then it will show you a summary of what it will do and ask you for confirmation. Type `y` for _yes_ and then press `Enter` for the installation to start.

|

||||

Let's install our first package!

|

||||

To do so, enter `sudo dnf install cmatrix`.

|

||||

You will be asked for the password of your user.

|

||||

Type the password and then press `Enter`.

|

||||

For security reasons, you will not be able to see you password while entering it.

|

||||

So don't wonder why nothing happens while typing the password.

|

||||

Just type it and then press `Enter`.

|

||||

|

||||

After the installation is done, you can enter `cmatrix`. Congratulations, you are a hacker now! 💻🤓

|

||||

The package manager might need some time to synchronize some data, then it will show you a summary of what it will do and ask you for confirmation.

|

||||

Type `y` for _yes_ and then press `Enter` for the installation to start.

|

||||

|

||||

After the installation is done, you can enter `cmatrix`.

|

||||

Congratulations, you are a hacker now! 💻🤓

|

||||

|

||||

To exit the matrix, press `q`.

|

||||

|

||||

What if you don't like the matrix and want to remove it? You can uninstall packages using `sudo dnf remove PACKAGENAME`. In this case: `sudo dnf remove cmatrix`. You have to confirm again with `y`.

|

||||

What if you don't like the matrix and want to remove it?

|

||||

You can uninstall packages using `sudo dnf remove PACKAGENAME`.

|

||||

In this case:

|

||||

`sudo dnf remove cmatrix`.

|

||||

You have to confirm again with `y`.

|

||||

|

||||

Why do we speak about _packages_ instead of programs when installing software on Linux? Because packages can contain more than one binary (the actual program) and extra files. Take a look at [the files that are installed with `cmatrix` on Fedora](https://packages.fedoraproject.org/pkgs/cmatrix/cmatrix/fedora-rawhide.html#files) for example.

|

||||

Why do we speak about _packages_ instead of programs when installing software on Linux?

|

||||

Because packages can contain more than one binary (the actual program) and extra files.

|

||||

Take a look at [the files that are installed with `cmatrix` on Fedora](https://packages.fedoraproject.org/pkgs/cmatrix/cmatrix/fedora-rawhide.html#files) for example.

|

||||

|

||||

> Warning ⚠️ : While installing or uninstalling packages, it is important to take a look at the summary before confirming the action with `y`. There is a reason why a confirmation is required. Sometimes, some packages depend on packages with older versions than the versions that exist on your machine. If you want to install those packages anyway, other packages that depend on the newer versions can break!

|

||||

> Warning ⚠️ : While installing or uninstalling packages, it is important to take a look at the summary before confirming the action with `y`.

|

||||

> There is a reason why a confirmation is required.

|

||||

> Sometimes, some packages depend on packages with older versions than the versions that exist on your machine.

|

||||

> If you want to install those packages anyway, other packages that depend on the newer versions could break!

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Just don't blindly press `y`. If the package manager gives you a warning before doing something, enter this warning in a search engine and read about what it means before continuing.

|

||||

> Just don't blindly press `y`.

|

||||

> If the package manager gives you a warning before doing something, enter this warning in a search engine and read about what it means before continuing!

|

||||

|

||||

### Sudo

|

||||

|

||||

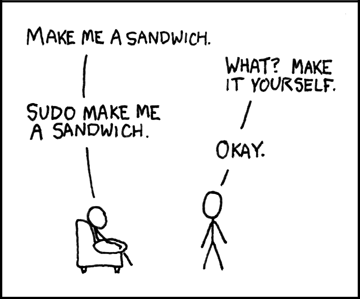

[](https://xkcd.com/149/)

|

||||

|

||||

Let's try to install another package, this time without `sudo` at the beginning of the command.

|

||||

Let's try to install another package.

|

||||

But this time without `sudo` at the beginning of the command.

|

||||

|

||||

```console

|

||||

$ dnf install cowsay

|

||||

|

|

@ -55,31 +90,44 @@ Error: This command has to be run with superuser privileges (under the root user

|

|||

|

||||

You can see that you get an error resulted by a lack of privileges for running this command.

|

||||

|

||||

Any action that might modify the system needs administrative privileges. Installing a package (system-wide) is one of these actions.

|

||||

Any action that might modify the system needs administrative privileges.

|

||||

Installing a package (system-wide) is one of these actions.

|

||||

|

||||

Sometimes, an action might not modify the system, but a user might be restricted through the permissions system to not be able to access a file for example. In this case, you would also need to use `sudo`.

|

||||

Sometimes, an action might not modify the system, but a user might be restricted through some permissions to not be able to access a file for example.

|

||||

In this case, you would also need to use `sudo`.

|

||||

|

||||

Linux has a superuser, one user that exists on every Linux system and is able to do anything! This user is the `root` user. For security reasons (and also to not do something destructive by a mistake), this user is often locked. `sudo` allows you as a non root user to run commands as a `root` user.

|

||||

Linux has a superuser, one user that exists on every Linux system and is able to do anything!

|

||||

This user is the `root` user.

|

||||

For security reasons (and also to not do something destructive by a mistake), this user is often locked.

|

||||

`sudo` allows you as a non root user to run commands as a `root` user.

|

||||

|

||||

You are not always allowed to use `sudo`. If you don't own the machine you are using and just share it with others, then there is a high chance that only administrators of the machine have `sudo` access.

|

||||

You are not always allowed to use `sudo`.

|

||||

If you don't own the machine you are using and just share it with others, then there is a high chance that only administrators of the machine have `sudo` access.

|

||||

|

||||

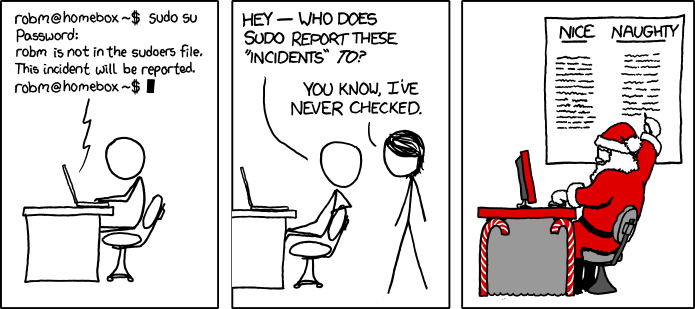

If you don't have access to `sudo` and try to use it, then you get an output like this:

|

||||

|

||||

[](https://xkcd.com/838/)

|

||||

|

||||

> Warning ⚠️ : Use `sudo` with great caution! Do not run a command from the internet that you don't understand! Especially if it needs to be run with `sudo`! RED FLAG! 🔴

|

||||

> Warning ⚠️ : Use `sudo` with great caution!

|

||||

> Do not run a command from the internet that you don't understand!

|

||||

> Especially if it needs to be run with `sudo`!

|

||||

> RED FLAG! 🔴

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Look up a command before you run it.

|

||||

> Look up a new command before you run it.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Even commands that you know like `rm` can destroy your system if you use them with `sudo` without knowing what they are doing.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> You might find a "meme" in the internet that tells you to run something like `sudo rm -rf /`. This command would delete EVERYTHING on your machine. It is like deleting the `C` and all other drives at the same time on Windows.

|

||||

> You might find a "meme" in the internet that tells you to run something like `sudo rm -rf /`.

|

||||

> This command would delete EVERYTHING on your machine.

|

||||

> It is like deleting the `C` and all other drives at the same time on Windows.

|

||||

>

|

||||

> Linux assumes that you know what you are doing when you use `sudo`. _With great power comes great responsibility!_

|

||||

> Linux assumes that you know what you are doing when you use `sudo`.

|

||||

> _With great power comes great responsibility!_

|

||||

|

||||

### Looking for a package

|

||||

|

||||

If you don't exactly know the name of a package you are looking for, then you can use `dnf search PATTERN`. DNF will then return packages that match the pattern in their name or description.

|

||||

If you don't exactly know the name of a package you are looking for, then you can use **`dnf search PATTERN`**.

|

||||

DNF will then return packages that match this pattern in their name or description.

|

||||

|

||||

For example, if you search for Julia (a programming language) you get the following results:

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

@ -104,9 +152,9 @@ perl-Date-JD.noarch : Conversion between flavors of Julian Date

|

|||

python3-jdcal.noarch : Julian dates from proleptic Gregorian and Julian calendars

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

If you know the name of the program but you don't know the name of the package that contains this program, use `dnf provides PROGRAMNAME`.

|

||||

If you know the name of the program but you don't know the name of the package that contains this program, use **`dnf provides PROGRAMNAME`**.

|

||||

|

||||

If you want to install the program `trash` (no joke) that provides you with the functionality of a system trash (instead of completely deleting), then you can run this:

|

||||

If you want to install the program `trash` (no joke 🗑️) that provides you with the functionality of a system trash (instead of completely deleting), then you can run this:

|

||||

|

||||

```console

|

||||

$ dnf provides trash

|

||||

|

|

@ -121,9 +169,10 @@ Matched from:

|

|||

Filename : /usr/bin/trash

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

You can see that the name of the package is not the same as the name of the program. Using `provides` makes your life easier while looking for the package to install.

|

||||

You can see that the name of the package `trash-cli` is not the same as the name of the program/binary `trash`.

|

||||

Using `provides` makes your life easier while looking for the package to install.

|

||||

|

||||

If you did find a package but you want to get more information about it, you can use `dnf info PACKAGENAME`:

|

||||

If you did find a package but you want to get more information about it, you can use **`dnf info PACKAGENAME`**:

|

||||

|

||||

```console

|

||||

$ dnf info julia

|

||||

|

|

@ -154,13 +203,19 @@ Name : julia

|

|||

Version : 1.7.3

|

||||

Release : 1.fc36

|

||||

Architecture : x86_64

|

||||

(...)

|

||||

(…)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

You get two results for Julia that seem to be identical. The difference is the _architecture_. Normal computers usually have the `x86_64` architecture, so you should look for it. But it is nice to know that other architectures are also supported.

|

||||

You get two results for Julia that seem to be identical.

|

||||

The difference is the _architecture_.

|

||||

Normal computers usually have the `x86_64` architecture, so you should look for it.

|

||||

But it is nice to know that other architectures are also supported.

|

||||

|

||||

If you have a problem with a package after an update, then you can try to use an older version. To do so, refer to the documentation of `dnf downgrade`.

|

||||

To run updates on your system, use **`dnf upgrade`**.

|

||||

|

||||

To run updates on your system, use `dnf upgrade`.

|

||||

For security reasons, it is important to run updates frequently!

|

||||

A package manager updates the whole system and its programs.

|

||||

This means that you don't have to update your packages separately.

|

||||

|

||||

For security reasons, it is important to run updates frequently! The updates installed using a package manager in Linux update the whole system and its programs. This means that you don't have to update your packages separately.

|

||||

If you have a problem with a package after an update, then you can try to use an older version.

|

||||

To do so, refer to the documentation of **`dnf downgrade`**.

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

@ -322,7 +322,7 @@ fi

|

|||

|

||||

<!-- TODO: Long command on multiple lines \ -->

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- Why ./SCRIPT_NANEM -->

|

||||

<!-- Why ./SCRIPT_NANE -->

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- TODO: Permissions -->

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

Loading…

Reference in a new issue